|

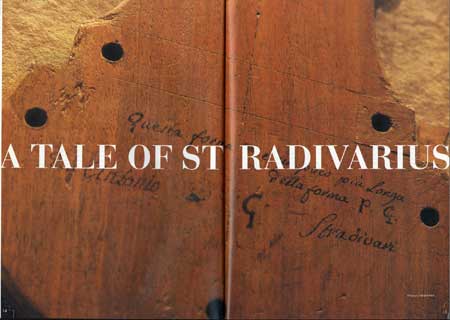

A TALE OF STRADIVARIUS

(Enlarged Image:167KB) |

|

Genius of violin making

original text in Japanese by Motoyuki Teranishi

"Stradivarius" is a Latin name for Stradivari and refers to the instruments made by Antonio Stradivari. An Italian luthier, Antonio Stradivari (1644?-1737) signed "Stradivarius" on the labels marking the instruments he made. Stradivari lived in a northern town of Italy called Cremona. Cremona had been for a long time the center of stringed instrument making and many luthiers, who have mastered the instrument making skills under the strict master-pupil mentorship, produced high quality stringed instruments.

The so called "Cremonese" violin-making began with the Amati family. Andrea Amati in the 16th century formed the shape of 'violin' as we know today. Andrea's two sons, Antonio and Hieronymus, and Hieronymus' son Nicola (1596-1684) were at the peak of Amati family of luthiers. Nicola's instruments with beautiful well thought-out carvings and elegant tonal quality greatly influenced the instrument artisans at that time.

Nicola Amati's most outstanding pupil was Antonio Stradivari. Antonio Stradivari trained under Nicola Amati since his teens and mastered the fundamental skills of instrument making. Stradivari was not satisfied simply to follow the footstep of the master's instrument making style. In 1680, Antonio set up his own shop in Brescia, town north of Cremona, also known for stringed instrument making. Also influenced by the Brescia's master artisan Maggini's powerful instruments, Stradivari began to search for his ideal instruments in his own style of violin making.

Since Antonio Stradivari began the work in his own shop, hi went through a continuous process of trial and error. Practically all-day from dawn to sunset, Antonio devoted himself to making instruments and continued searching for ways to make better instruments. He was a true craftsman and did not get satisfied easily. Through making many violins, cellos and violas he studied numerous combination possibilities of the shape, contour of the instrument body, thickness of the wood, wood material and the varnish, in pursuit for his ideal instrument.

Looking at the activities of Stradivari, the years 1680-1690 is often referred as "Trial Period" (though many masterpiece instruments were produced during this period) followed by the so-called "Golden Period" of 1700-1720. During the "Golden Period", Stradivari produced the most outstanding and the most elegant instruments using maple with beautiful grain in carefully thought-out thickness. The Stradivarius' exquisite varnish, said to affect the sound quality, is still a mystery as to its composition and how it was applied. The masterpiece Stradivarius known for their tonal beauty and colourfulness are the culmination of the craftsmanship of pursuing the ideal to perfection. Even after the "Golden Period", Stradivari's violin making skill did not deteriorate and Stradivari continued to make the masterpiece instruments even beyond the age of 90 years old.

When we speak of "Cremonese" instruments, we cannot forget to mention Guarneri del Gesu (1698-1744). His full name is Bartolomeo Giuseppe Guarneri and he is referred to as "del Gesu" taken from the label he placed inside the instrument marked with a cross and the cipher 'HIS' depicting Jesus or Gesu in Italian. He is recognized as the most illustrious violin maker of his family and the masterpiece "Guarneri" is referred only to the instrument made by del Gesu. Del Gesu, having the influences of the Stradivari and Maggini's violin making, pursued his unique style of violin making. The year 1735 being at his peak, del Gesu produced masterpiece instruments with tonal depth, powerful sound and ability to withstand strong bow pressure. The "del Gesu" instruments are regarded comparable to Stradivarius and many virtuosos of the 19th century played the "del Gesu" instruments including Niccolo Paganini (1782-1840).

The Cremonese violin making skill has been passed onto different parts of Italy by the pupils of Amati and many good quality stringed instruments were produced in Italy during the late 17th century and early 18th century: Grancino and Testore of Milano, Gagliano of Napoli, Monta-gnana and Gofriller of Venice, Carcassi of Florence, as well as Guadagnini to only name a few. However, when Carlo Bergonzi, pupil of Stradivari, passed away in 1747 and Pietro Guarneri in 1762, the glorious era of Italian violin making came to an end.

From the late 18th century to 19th century, the violin making became popular in France by such artisans as Nicolas Lupot (1758-1824) , Francois Tourte (1747-1835) who is famous for his bows, and Jean-Baptist Vuillaume (1798-1875) who was also a famous violin dealer. However, it happened to coincide with the era of mass production, and artisans did not focus on producing unique instruments individually in comparison with the Italian artisans. It is unfortunate that another "Golden Period" of instrument making was not attained.

interview

Andrew Hill's out of ordinary love towards instruments wins great trust from the world's players and collectors.

Interviewed by Yoshiyuki Tanaka

Andrew Hill

Why are people attracted to Stradivari instruments?

Stradivari instruments are firstly superb musical instruments, and secondly, they are works of art, that are attractive to look at. The way the instruments were carried about, slid into cases on end, meant that the varnish used to get worn off, which, particularly on the back, gave rise to the wonderful contrast between the colour of the top varnish and the base coat. No two violins, or other instruments are quite the same, and this is what gives an unusual charm to the beholder. You also have to remember that Stradivari made a large number of instruments and every single one was to the same extraordinary high standard. The violin family was perfected in Italy during the 17th and 18th centuries, through the Amatis, the Guarneris, and Stradivari, and all of them made the best, but Stradivari's output was not only consistently superb, but it was the most prolific. When the violins and so on were new, we have the proof from contemporary letters that it took quite some forty years for the sound to really develop, but unlike with a good wine, which has a finite life, the Stradivarius and the others went on improving; and you cannot therefore, make a reasonable comparison against a new instrument from today.

It is said that there are over 700 Stradivarius in the world and quite a number of them are in Japan.

Unfortunately, I have to say that the Stradivarius that went out to Japan in the early days, were sometimes rather dubious examples; with relatively little knowledge in Japan about this type of musical item, and here I am talking about the 1950's onwards, certain unscrupulous traffickers took advantage, and some awful things were perpetrated on unsuspecting players. The condition, the originality, the history, all these things play a part in assessing the value, and some of the early sales to Japan were at much inflated prices for the quality of the item concerned. Tone, however, is very difficult to quantify, and that we never put a value on; but a good violin, that has not had any invasive repairs, will always be more valuable, and also more reliable in the hands of the player as it travels around the world. The good thing is that the Japanese are now fully aware of what they should be looking for!

Can you tell us the name of the best instrument by Stradivari?

When I joined the family firm, one of the first things I learnt, was "DAM", the three violins that we considered as the absolute tops; and that is "D" the 1714 "Dolphin" the "A" is the 1715 "Alard" and the "M" is the 1716 "Messiah". The first used to be Heifetz' violin, and is now with the Nippon Music Foundation; the "Alard" is in private hands, and the "Messiah" is in as new condition, and was given to the British nation to go on display in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. My family donated it, as we wished its pure state of preservation to be guarded for the benefit of future generations.

What is the most expensive Stradivari you have handled?

That is an awkward one! Ones I can talk about, as some are not public, would be the 1721 "Lady Blunt" which we acquired for a customer in 1971 for £84,000 (208,000 US dollars at the time) and then there was the "Alard" mentioned earlier, at 1,250,000 US dollars some ten years later; the "Paganini" quartet was fifteen million dollars ten years ago, and so on; my partnership has recently sold some very good examples in excess of the five million dollar range. It is worth saying that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, valuable musical instruments were largely confined to "Old Europe" and they were not generally for sale in the USA, Japan or anywhere else; but as more and more people around the world have taken up music, the market has become a global one and scarcity and demand has steadily inflated prices.

How do you determine if an instrument is a genuine one or not?

Rather like recognizing a person's handwriting, and whether or not there is a label inside, is the last thing we look at; apart from the fact that labels can be very easily removed, it is the way the wood and model are worked, the varnish, and the quality that make the impression on an expert. Curiously, perhaps, the tone is not a matter that we assess; this is always 90% the player.

The "Messiah" was condemned by a leading American museum director as a "French fake" and you can imagine we took great exception to this; one recent development in our field that has helped confirm authenticity is the science of dendrochronology. This is the accurate measurement of the distance between the year rings on a plank of spruce, such as is used for the top of violin family instruments; the measurement can give us an exact date for when the tree was alive; the rings vary in width according to the amount of rainfall in any given year, and this has been mapped internationally. In the "Messiah"s case, not only is the wood correct for the period, it matches the wood of the 1717 "Sasserno" owned by the Nippon Music Foundation. The violin is in such new and unworn condition, that amateur "experts" refuse to believe that it is genuine. My firm felt that since Stradivari had perfected the form and finish of the violin, it would always be important to have a pure example to learn from; and unfortunately, wear takes place, accidents happen, and it will be more and more difficult in the future to know what a violinmaker should be striving for if there is not a perfect model to follow.

It is said that Stradivari had two sons. Were they helping in his workshop?

Yes, Francesco and Omobono. They were in their thirties and twenties when their father was at the height of his powers. When we say "Stradivari" today, we refer only to instruments made by Antonio as the output of his workshop; the sons would have played a big part in that. Later, there are individual instruments known, but of the two, Omobono is rather lacking the skill of his father.

Does that mean that the sons' instruments are not as expensive as the father's?

That is correct. Difficult to quantify, and there will always be exceptions, but perhaps eighty or ninety percent less.

Are instruments by Guarneri del Gesu as superb as Stradivarius?

Yes, but in general, they tend to have a different timbre of sound that some artists prefer. My old friend, the late Isaac Stern, always played on a Guarneri. One day, I showed him a Stradivari that the firm had, which was reputed for its particularly "bold" tone, and after he had played it for a while, he remarked that 'it was as good as his Guarneris', he was not expecting to hear that quality of sound; but the output of Guarneri is small compared to Stradivari.

PROFILE◎The Hill family has been in the instrument business since the 18th century. After acquiring the instrument making techniques in Paris, joins the family firm W.E.Hill & Sons.

Donated the purest Stradivarius called 1716 "Messiah" to the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford in 1950. Started his own W.E.Hill firm in 1991.

Handling many masterpieces for many of the world's most outstanding players and collectors..

Instrument advisor to Nippon Music Foundation. |

Does the tonal quality improve if they are constantly played?

It is not necessarily good to have an instrument played constantly, and it is good to rest them occasionally; letting the strings down a semi-tone, just to take the full tension off, is a help, and of course, supposing that there is another violin to use. The pull of the strings totals some 50kg, and it is a tribute to Stradivari and the other makers that instruments today can stand present pitch levels without collapsing. However, if the pitch is raised further, the strain may be too much for many instruments, and should not therefore be allowed.

Is it difficult to maintain these instruments?

Human perspiration is probably the most damaging to any instrument, as it can cut through the original varnish if not checked; all the items in use today are only in the hands of temporary custodians, so there is a terrific responsibility to treat each one with the greatest care and consideration.

How difficult is it to repair them?

Sometimes quite difficult, but they were all designed to be taken apart without destroying them, the makers realized that repairs would be inevitable at some stage. The most complicated I have seen, was the Stradivari violoncello that was on a ship that got sunk in the South Atlantic, and fortunately it was washed up and found onshore in its Hill case, but by this time, completely unglued. The firm eventually, after eight or nine months' work, put it all back together, and the owner pronounced it better than before. To be fair, it was beginning to need a serious overhaul, but he had never felt he could be parted from it.

Who do you think makes the best sound on a Stradivari?

As I should like to go on living, may I pass on that question?

Do you have a Stradivari that you are considering acquiring next?

There are instruments that I know, and of course you always wonder if they are not being used whether perhaps they are likely to come onto the market; but mainly it is the element of surprise. I recently had a call from someone who wanted to sell urgently that morning, and by the afternoon, the violin was with a new owner, and paid for, too. But, no, I could not say if there was anything specific at the moment!

|