| THE SPECIAL AMBASSADOR'S JOURNAL |

|

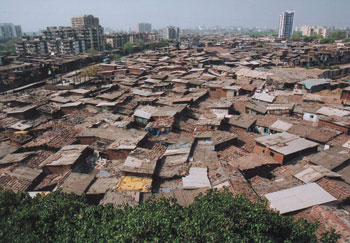

| Residents of a colony in Orissa |

| |

India

Orissa (July 7-9, 2003) |

In July, I went to the northeastern state of Orissa. After Bihar, it is the state with the highest prevalence rate in India, with 7.3 leprosy patients per 10,000 inhabitants at the time of my visit.

Of Orissa's 30 districts, nine have a prevalence rate of more than 10 per 10,000. Political leaders such as the governor, chief minister and health minister are keenly committed to eliminating leprosy. Meanwhile, integration is moving ahead and MDT is widely available. Nonetheless, in the past 10 years, not much progress has been made. Why?

There are three major problems, the first relating to urban areas, the second to border regions and the third to tribal areas. The prevalence rate in urban areas is more than double that in rural districts, and particularly bad in the urban slums that account for 13% of Orissa's population. Next, 34 of the state's 314 blocks are situated in border areas where patients frequently move back and forth across the state line. For a long time, healthcare services in these rural border areas were inadequate; furthermore, MDT was only introduced to these areas in 1994, and full statewide coverage wasn't achieved until 1997. Finally, proper information about leprosy is not getting to the tribal peoples who make up 22% of the state's population. Enhancing interpersonal communication programs is crucial to reaching them.

Faced with these adverse conditions, a four-step milestone plan to eliminate leprosy, district by district, before the end of 2005 has been drawn up under Governor M.M. Rajendran. With the governor leading the way, I sense an enthusiasm for the task not seen in other states. I hope that all involved will step up their efforts to make the plan a success.

Visiting a leprosy hospital-cum-colony of about 200 people, I was struck by the fact that there were young women and children there who are completely cured. That they are living in unnecessary isolation is proof of the social stigma attached to them. In addition to the drive for leprosy elimination, therefore, we need a separate effort to ensure such people can be welcomed back into society. |

| |

| West Bengal (November 11) |

In November, I visited Kolkata, Delhi, Wardha and Mumbai. In Kolkata I went to Garden Reach, an urban slum of 300,000 people with a population density of 30,000 per square kilometer. In the slum clinic I found neatly organized records going back 26 years for as many as 8,000 leprosy patients who had been treated there. I have nothing but admiration for the dedicated efforts of the staff over such a long period. The clinic also acts as an NGO office, and provides micro-financing for people affected by leprosy to help them start their own small businesses. So as well as treating patients, it is also helping them to become self-reliant once they are cured, and as such serves as a very good example of how to encourage social participation.

Elimination activities in West Bengal generally seem to be making good progress, although from what I have seen there are still a few problems. First, there are flaws in the management of MDT. The availability of drug supplies at Primary Health Centers varies, and there are insufficient stocks of children's dosages−a point I was asked to convey to the relevant authorities in Delhi. Second is the problem of defaulters−patients failing to complete treatment. With the integration of leprosy services into the general healthcare system in Kolkata, responsibility for case-holding has passed to local government. As a result, many patients have had to change the clinic where they go for treatment, or have found that they have been inadvertently dropped from the treatment list. Clearly, it will be necessary to conduct a review of patients to track down anyone who might have been overlooked in the changeover. |

| |

|

| Children in Garden Reach, Kolkata |

| |

| Maharashtra (November 12-19) |

| |

|

| A woman learns how to weave at Shantivan Nere, Maharashtra |

| |

In the central Indian city of Wardha in the state of Maharashtra is the Sevagram Ashram where Mahatma Gandhi lived from 1936. Gandhi regarded leprosy as a challenge to humanity and was associated with the disease for over 50 years. He once said, “Leprosy work is not merely medical relief; it is transforming the frustration of life into the joy of dedication, personal ambition into selfless service.” This place is home to the Gandhi Memorial Leprosy Foundation. Established in 1951, the foundation focuses in particular on education and health training programs in areas where the prevalence rates are especially high. When the foundation began its work, the prevalence rate in Wardha District was 233 per 10,000. Since the introduction of MDT, it has dropped to 3.4 per 10,000.

I visited Mumbai from November 16 for four days. Maharashtra has a population of more than 100 million, of whom 42% live in cities, and the rest in 42,000 villages scattered all over the state, many of them in areas that are extremely difficult for the health services to reach. In 1981, the prevalence rate for the whole of Maharashtra was 62.4 per 10,000, but today the figure is down to 2.75. There remain three barriers to elimination: the inaccessible tribal regions and remote areas, the slums that account for 65% of the urban population and the difficulty of keeping track of the movements of people in border areas.

The state is currently promoting a special action plan to address these difficulties. I was very encouraged by my meeting with Chief Minister of State, Shri Sushilkumar Shinde, who told me that both he and the chief secretary have taken it upon themselves to form a committee consisting of state representatives from education, labor and industry as well as representatives from NGOs to tackle leprosy problems in the state. I also received assurances from State Governor, Shri Mohammed Fazal, and State Health Minister, Shri Digvijay Khanvilkar, of their firm intention to work toward the elimination of leprosy, and verified that the state government is committed to this goal at the highest level. The strategy drawn up by the health ministry has been well formulated, and all that remains is for it to be implemented.

Mumbai is home to Asia's biggest slum, Dharavi. Some 600,000 people from all over India live here, and the population density is as high as 60,000 per square kilometer. The Bombay Leprosy Project has been working here since 1979. In 1983, the prevalence rate in the slum was 22.4 per 10,000; by August 2002, it had dropped to 0.7 per 10,000. This dramatic decrease is thanks to the devoted efforts of project members. This NGO not only seeks out and treats patients; it helps in the socio-economic rehabilitation of leprosy-affected people who have made a complete recovery, with support from local companies offering vocational training.

To clear up society's misunderstandings about leprosy, it is vital to involve the non-leprosy community. I visited the Maharashtra Chamber of Commerce to meet with the president and other officers and ask for their support in disseminating correct information on leprosy to their members. I also had the opportunity to address the oldest Indo-Japanese association in India about my mission. Afterward some young ladies in the audience asked questions such as, “Is it true that leprosy is hereditary?” or “Is it true that leprosy is dangerous because it's a communicable disease?”, and I realized that ordinary people still know far too little about leprosy and that much more needs to be done to educate the nonleprosy community. |

| |

|

| Dharavi, the biggest slum in Asia |

| |

| It goes without saying that strong political will, the commitment of all people from central government officials to local health workers and a feasible strategy are necessary for elimination. But even more important is the necessity to reach out to society, disseminate accurate information and get each person to feel that elimination is his or her responsibility. I have no doubt that India, where Mahatma Gandhi made such a contribution to acknowledging the human dignity of those with the disease, will succeed in eliminating it once and for all. |

| |

| Cambodia (December 4) |

| |

|

| Meeting a patient at Kien Khleang Center, Cambodia |

| |

I met Dr. Mam Bunheng, secretary of state for health, at the Ministry of Health in Phnom Penh. Cambodia achieved the elimination target in 1988, and the current prevalence rate is 0.47 per 10,000. Secretary Bunheng told me that in undeveloped areas of the country, particularly the difficult-to-reach mountainous regions, the monitoring system is being strengthened and elimination activities are ongoing. I also had the opportunity to visit Kien Khleang Center, a facility for disabled people offering surgery and rehabilitation. I spoke with about 40 leprosy patients being treated there. The aftereffects of their disease were such that almost all of them required surgery, but with the fine treatment they are receiving from Dr. Stephen Griffiths of the CIOMAL−Comite International de l'Ordere de Malte, the aim is to help them return to society at an early date.

Sustaining what has been achieved and ensuring the social rehabilitation of leprosy-affected people are critical tasks to be continued beyond 2005. The fight against leprosy is never-ending, and I have renewed my determination to devote my life to this battle. |

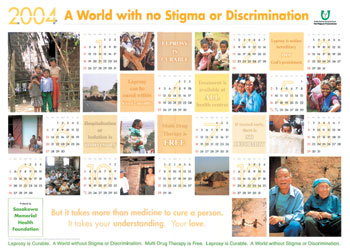

The Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation (SMHF) has prepared wall calendars for 2004 and 2005 entitled “A World with No Stigma or Discrimination.” The 2004 calendar features messages relevant to the fight against leprosy, such as “Leprosy can be cured within 6 to 12 months” and “Leprosy is neither hereditary nor God's punishment,” while the 2005 calendar is based on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The 60cm x 42cm calendars are available free of charge by contacting the SMHF office at 1-2-2 Akasaka, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-0052, Japan (Fax: +81-3-6229- 5388, Email: smhf@tnfb.jp). Please include the words “Calendar Offer” in the subject heading. |

| |

|

| |

| WHO Special Ambassador's Newsletter |

| No. 6, February 1, 2004 |

|

| |

| Publisher |

Editorial Office |

| Yohei Sasakawa |

WHO Special Ambassador's Newsletter |

Editor in Chief

Tatsuya Tanami |

5th Floor, Nippon Foundation Building |

| 1-2-2 Akasaka, Minato-ku, Tokyo 107-8404, Japan |

Editor

Jonathan Lloyd-Owen |

Telephone: +81-3-6229-5601 Fax: +81-3-6229-5602 |

| Email: smhf_an@tnfb.jp |

| Contributing Staff |

With support from: |

| James Huffman, Akiko Nozawa |

Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation; |

| Photographer |

The Nippon Foundation |

| Natsuko Tominaga |

Back issues of the newsletter are available at:

www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/eng/ |

| If you change your mailing address, please let us know so we can

update our mailing list. |

| Contributions or comments should be addressed to the Editorial Office as listed above. |

|

| (c)2004 The Nippon Foundation. All rights are reserved by the foundation. This document may, however, be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, but not for sale or for use in conjunction with commercial purposes. The responsibility for facts and opinions in this publication rests exclusively with the editors and contributors, and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the Special Ambassador's Office. |

|