Country Scene in West Bengal

|

| REPORT FROM INDIA |

|

Pilot Project at School in Uttar Pradesh

by Leena Nandan |

| Leena Nandan was project director for the National Leprosy

Elimination Program, in the state of Uttar Pradesh (UP) in 2002-2003. Her previous

positions for the Indian Administrative Service include Managing Director for

Women's Welfare, UP, where she was responsible for formulating the Women's Empowerment

Project. Ms. Nandan has extensive experience in working for rural and urban poor.

The following article highlights a successful and practical approach to fighting

leprosy. |

| |

|

| Amarnath, a bright and alert child, 10 years of age, takes school very seriously. His family belongs to the urban poor strata of society and, although most of his brothers have attended school, they have had to drop out due to economic reasons. |

| Amarnath is the second-youngest sibling in a family of four

boys and one girl. Despite the fact that his second brother was diagnosed with

leprosy a few years ago and underwent treatment as a PB (paucibacillary1)

case, their mother did not realize that the telltale patches on her own skin,

as well as Amarnath's, were indicative of the fact that they were also MB (multibacillary)

leprosy cases. It was only the School IEC2/Diagnostic

campaign, launched as a new initiative in the government-run primary schools of

urban Lucknow (the capital of UP), which brought these hidden cases to light.

When Amarnath was asked why he responded to the IEC card distributed in the school,

his simple answer was "Because my teacher asked me to take the card home and show

it to my mother." What exactly is this IEC card, and what is this pilot project

? |

| Pilot Project Background |

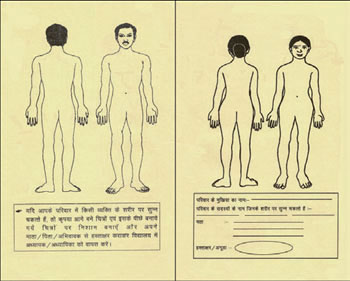

| Yohei Sasakawa, president of The Nippon Foundation and WHO Special Ambassador for the Elimination of Leprosy, visited Uttar Pradesh (a northern state of India − population 166 million) on December 6th and 7th, 2002. In the course of discussions held at that time, Mr. Sasakawa suggested that since school-children are an invaluable medium for IEC, they could be used even more effectively. In order to attract their interest and make the IEC effective, a new format based on drawings of the human figure could be developed. On the basis of this idea, a school IEC card was designed and printed as a two-page leaflet. On the cover page is a drawing of a male figure and on the reverse, a female figure. Simple instructions have been given on the cover, explaining that if anyone in the family has skin patches lacking sensation, their location should be indicated by sketching a patch on the figure. On the reverse side of the cover, below the drawing of the female figure, there is space for the name and address of the child, names of people having skin patches and space for the signature/thumbprint of the parent/guardian. |

| |

|

| |

| The second page of the card is detachable, and has information on leprosy, namely that it is fully curable, drugs are available at all government health centers free of charge, and so on, written on both sides. The detached part is to be retained by the child, so that he/she can read the messages later, and continue to benefit from the information. |

| |

Social Workers in Uttar Pradesh |

| |

| This IEC card is distributed to schoolchildren by schoolteachers and health workers, who explain its purpose to the children. On taking it home, the children tell their parents what the symptoms described on the card are and how the card has to be filled in. They then return the card to their teacher. All the returned cards are collected by a health worker from the school and studied to see which of them have skin patches indicated. These are followed up individually, and after the medical officer confirms the diagnosis, treatment is started. |

| Pilot Project |

| With a view to utilizing this IEC/diagnostic school card, a pilot project was initiated in the urban areas of Lucknow. It was launched by the Principal Secretary of Medical, Health and Family Welfare (of the Government of UP), on January 30th, i.e. Leprosy Day. After the cards were distributed, the children held a rally, holding placards on leprosy and its cure. |

| During Leprosy Week, 17,268 cards were given to 216 government schools in the urban areas of Lucknow, and distributed to students from third grade through eighth grade. This was done with the joint efforts of health workers and school authorities in coordination with the Basic Education Department. A total of 15,114 cards were then returned by the children to the teachers. Each card was examined to see what the children had indicated. 276 of the returned cards indicated skin patches. So in the months of February and March, each suspected case was investigated and, after diagnosis, eight people were confirmed as leprosy patients. |

| Out of these eight cases, one patient, whose daughter had drawn patches on the card, indicated that he had been diagnosed in October 2002 and was already receiving treatment. The remaining seven were new cases. |

| Of these eight patients, six are living either in urban slums or in nearby villages. Four are from a low-income group and four are living below the poverty line. When asked individually, they said that messages in the form of banners, handbills, billboards and advertisements have no impact. Similarly, they do not listen to verbal announcements, and even if they do, for the most part they are unable to comprehend the messages. The parents are illiterate or semiliterate and were diagnosed only because the children faithfully followed the instructions given by the teachers during the School IEC. |

| The paramedical workers who were involved in the above IEC/ diagnostic activity expressed their view that this was a useful and effective way of detecting patients. Since children played a key role in the detection, they will take an active role throughout the treatment process, thus reducing chances of default. |

| |

Children in West Bengal |

| Conclusions/Recommendations |

| School IEC activities so far have been confined to organizing debates, quiz competitions, and the physical examination of schoolchildren. No doubt physical examination of children leads to detection, but the advantage of a focused school IEC/diagnostic campaign is that it simultaneously addresses the schoolchildren and their family members. |

| The cost of printing the 17,268 cards at the rate of 23 paisa per card was only 3,979 rupees ($87). This proves that result-oriented IEC need not necessarily be cost intensive. |

| Any media tool for IEC should be designed with the impact of the tool in mind. Identification of the target group (in this case children and families) and the best way to approach them has to be the underlying strategy. |

| Traditional methods of IEC such as distribution of handbills, banners and billboards cannot reach that part of the target population which is illiterate. Verbal announcements are also not very successful, as many people are unable to comprehend the messages broadcast via loudspeakers. |

| Since 36% of the UP population lives below the poverty line, they are unable to benefit from TV spots. Either they don't own a TV or they are too preoccupied with their daily needs to listen attentively. |

| A few additions to the School IEC can be made in order to enhance the impact. The children could be given a pencil each to stimulate their interest. Also, instead of relying only on the health workers to explain the exercise to the teachers, printed guidelines could be circulated to the teachers as well, enabling them to understand the campaign better, and guide the children accordingly. |

|

| 1 |

Leprosy is classified as paucibacillary or multibacillary leprosy based on the number of patches. PB is usually non-infective while MB is infective. |

| 2 |

IEC − Information, Education and Communication |

|